Learning from theory can only take you so far

“I forget what I was taught. I only remember what I have learnt.”

Patrick White, Nobel Prize winning author

I looked on, transfixed. My tutor almost radiated gentle encouragement as his client, a solitary tear trailing mournfully down her face, described an aching memory from long ago that she just couldn’t let go.

My tutor wasn’t just demonstrating therapy – he was helping change a life, right there and then. This wasn’t some dry discourse, some ancient theory on how people are supposed to act. This was the beating heart of therapy. This was dynamic, red-blooded learning. And I loved it.

“This was the beating heart of therapy. This was dynamic, red-blooded learning. And I loved it.”

Little did I know that as I watched the woman’s problem resolve before my eyes, I was absorbing a guiding principle that would stay with me for the rest of my career.

But the mysterious wheels and cogs of life revolve. And fifteen years later, I’m the tutor demonstrating therapy. After a recent session, a practising counsellor approached me and told me:

“I need to learn like this, because my brain is an image processor, not a word processor.”

“I need to learn like this, because my brain is an image processor, not a word processor.”

Now, this concept wasn’t new to me. Over the years I’d heard many variations on that theme. But this struck me as a really neat way of describing the vital importance of actually seeing therapy done – the power of visual learning. She’d perfectly put into words the principle I learned all those years ago. The principle I’ve stood by ever since.

When I was teaching the Diploma of Psychotherapy at the University of Brighton, we always tried to demonstrate everything we taught. We did this because we recognized that many people are visual learners, and gain at least as much from seeing something done as from reading about it. Especially if that reading material is dry and academic. Just as there’s more to life than theory, there’s more to therapy too.

“Just as there’s more to life than theory, there’s more to therapy too.”

Tweet “Just as there’s more to life than theory, there’s more to therapy too.”

On learning by osmosis

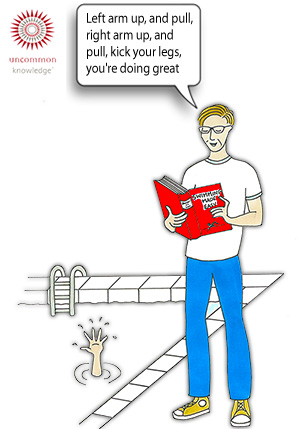

When I think back to when I was first learning therapy in the early 1990s, what really stands out in my mind now are the demonstrations of therapy and the descriptions of real therapy being done. Don’t get me wrong – a working understanding of current psychological knowledge is vital, and there are some excellent books and tutorials which are really important – but the written word is still a far cry from the real-life application of therapeutic skills.

Seeing knowledge applied is an irreplaceable part of training. From the moment we are born, we learn primarily through observation – “picking up” knowledge almost without knowing it. This is the traditional way of gaining knowledge for a reason – because it is the way we evolved to learn. And with the invasion of psychology by scientism, we are in danger of losing this ancient method of “learning by osmosis.” Here’s what I mean:

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

For hundreds of years people worked with an apprentice system, in which a student would live with a master, constantly observing his or her approach, movement, language, and skill. The apprentice would pick up the skills of the practitioner through association and observation.

The evidence that the student had picked the knowledge up was in his ability to perform the skill. Not a mark on a test! This seems to me to be a much more rational way of learning and measuring performance in the field of therapy than book learning.

Our Western, “left-brain” attitude to learning requires us not just to learn, but to know what we have learned. By these standards, unless we demonstrate the ability to reproduce facts, we haven’t learned anything.

In a world so focused on learning facts and figures, the ancient practice of learning simply by associating or watching someone can seem kind of strange. Indeed, when you only have one part of a puzzle, it can be hard to envisage the other – but the puzzle won’t be complete until you have both parts. Book learning and observational learning are both vital to the acquisition of deep learning.

Expertise, skills, and knowledge can be caught as much as taught.

“Expertise, skills, and knowledge can be caught as much as taught.”

Tweet “Expertise, skills, and knowledge can be caught as much as taught.”

The two paths to knowledge

Theory plus experience equals knowledge

Think now about your sharpest memories. What do they have in common? You might notice that these memories are not about things you have read, or heard about, but things you have seen. Myriad studies have proven how powerful visual learning is (1) (2) (3). But this only serves to back up what most people know intuitively: we learn best through observation.

There exists a wide range of learning types, but for now, let’s break them into two broad categories. First, there’s the sequential, step-by-step, note-taking type of learning: what we might call “left-brain” or “informational” learning. Then there’s the more holistic, big-picture type of learning: what we might call “holistic absorption.” Both types are equally important, yet in the West we tend to value the first type over the second. Personally, I refuse to advocate one type of learning over the other – and here’s why.

A question of degree

All fields of knowledge require both types of learning, but in different proportions. Learning accountancy or mathematics will require more of a left-brain approach to learning, with less (but still some) of the absorptive type of learning. A master mathematician’s attitude to their expertise can be subliminally picked up by the student, but a talented mathematics student is still likely to acquire a large part of their knowledge purely from books.

Social or physical skills such as fencing, dancing, or customer service will have some step-by-step stuff (quite literally in the case of dancing!) that can be learnt from books. But this is usually a poor substitute for watching it done by someone who has the skills you want to learn. In these kinds of fields, it’s easier to form a mental blueprint from watching rather than just reading or listening. And there’s one field in particular where this mode of learning is at least as important as the theory. I think you know what I’m going to say!

A crying shame

“Therapy is not an academic discipline. It is a practical trade.”

Tweet “Therapy is not an academic discipline. It is a practical trade.”

Therapy is not an academic discipline. It is a practical trade – a trade whose end product is an outcome rather than a commodity, but a trade nonetheless. Therapy is perhaps the most right-brain, intuitive human endeavour there is. So why do so many therapy schools treat it like a theoretical academic pursuit? Why aren’t they putting the necessary emphasis on learning by watching? It’s a crying shame, and it makes me worry for the future of the trade.

I was lucky in that my training consisted of all kinds of knowledge acquisition – hearing about case studies, reading, but above all, watching therapy being applied. For that, there is no substitute. I despair every time a trained therapist comes to me lacking in confidence simply because their tutors did not demonstrate enough real therapy with real clients.

Of course, therapists do need to learn step-by-step skills, the theory of how the mind processes emotion, and up-to-date research in the field of psychology. They do need to understand how beliefs are formed if they are to effectively challenge those beliefs when they become damaging.

But when you are actually doing therapy, all that knowledge needs to fall to the back of your mind. To be effective as a therapist, you need to be able to act intuitively and spontaneously with your client. Just as you don’t think about the alphabet when you’re reading a page-turning thriller, nor should you think about theory when you’re in the midst of practice. And speaking of books you’d love to read…

Writing the book you’d love to read yourself

They say you should write the book you’d love to read. Years back, not long after I’d qualified, I dug up a few dusty old VHS videos (remember those?) of therapy being applied with actual clients. Remembering how valuable observing therapy had been for me as a student, I watched them and watched them until they wore out! And then I found myself with little opportunity to keep learning through watching.

When I turned to teaching, we demonstrated live therapy on our courses and provided a therapy video library for students to borrow from. But the videos would often get lost or damaged, and some students would have to wait weeks before they could finally watch the video they wanted.

Back in my early days as a therapist, I would have loved a resource that let me choose to watch therapy being done whenever and wherever I wanted – without having to find a video or wait until someone lent me one. To see and be inspired by real therapy for depression, overeating, trauma, low self-esteem, addiction – whatever the case may be – at the click of a finger, maybe even just before a client arrived.

And now that resource exists – because we’ve made it. My team and I have worked for over two years to produce an exhaustive library of filmed client sessions, all in one place, available anytime, anywhere, to any therapist.

This is what I wished I’d had all these years: full sessions with real clients, as well as a range of shorter clips to concisely demonstrate specific therapy techniques. I knew that if I would have loved this resource, then others would too. At last, I’ve produced the “book” I’d love to read – or, to cast metaphor aside, the online resource that I wish I’d had way back when (though the fact that the Internet did not yet exist may have posed something of a barrier!).

The human heart of therapy

Trying to learn to be the best therapist you can be without watching lots of therapy (and really getting involved in the ‘story’ of the client) turns the whole thing into an academic exercise and may take the living, beating heart from what should be, above all, human.

I’ve read millions of words on therapy, psychology, neurology, sociology, and anthropology – and they’ve all helped me as a therapist. But what inspires me most is the therapy I’ve witnessed, whether in the flesh or on film. The skills, creativity – and yes, the mistakes – of other therapists. I learn visually and inspirationally, not just academically.

For me, a million textbooks wouldn’t begin to replace the human heart of real interaction.

What practitioners said

We also asked over 1500 of our practitioners whether they had seen live therapy as part of their training. You can see what they said here.

And you can find out about our visual learning CPD platform Uncommon Practitioners TV here.

Notes:

Patton, W. W. (1991). Opening students’ eyes: Visual learning theory in the Socratic classroom. Law and Psychology Review, 15, 1-18. McDaniel, M. A. & Einstein, G. O. (1986). Bizarre imagery as an effective memory aid: The importance of distinctiveness. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 12(1), 54-65. Verdi, M. P., Johnson, J. T., Stock, W. A., Kulhavy, R. W., & Whitman-Ahern, P. (1997). Organized spatial displays and texts: Effects of presentation order and display type on learning outcomes. Journal of Experimental Education, 65, 303-317.