There is an element of truth in all therapeutic factions, but it is the ability to discern the bigger picture that makes a good therapist

“Each person is an individual. Hence, psychotherapy should be formulated to meet the uniqueness of the individual’s needs, rather than tailoring the person to fit the Procrustean bed of a hypothetical theory of human behavior.”

– Milton H. Erickson, M.D.

It’s confusing.

There are hundreds of different psychotherapeutic models, but a finite number of types of emotional problems.

Which to choose? Which to use? How do we make sense of it all? What psychological help do people really need?

If you work with clients, maybe you sometimes wonder whether the help you give them is the best possible emotional help they could be getting.

Prefer to watch instead?

It’s really useful to see everything in context.

In this piece I want to help contextualize some of the main models for human emotional help, to look at where these ideas came from, and to evaluate where we seem to be at now.

It will be far from complete, but hopefully it will be sweeping enough to cover all the main aspects so you can see where your ideas and practices might fit into the overall scheme of therapeutic ideology.

It’s useful to see where our ideas and assumptions come from. For our clients, certainly, but also for us.

So let’s get to it.

Pre-verbal soothing

Psychotherapy, the ‘talking cure’, is not new. For as long as human beings have eased troubled minds through verbal communication, or even non-verbal soothings, a kind of psychotherapy has existed.

Our pre-language hominid ancestors were just as social as we are – even in the absence of Facebook! For thousands of years before written language, people told stories. And some of those would have acted as a kind of therapy.

The right story at the right time can heal as well as pass on wisdom as to how to deal with the patterns we encounter in life. Highlighting everything from heroism, good, evil, and temptation resistance, to transcendence of body and spirit and the power of resourcefulness and resilience, stories have contained all the truths in the world. Perhaps all the truths that can be in the world.

I see stories as kind of cultural packages of mental stimulation and metaphorical instruction and reframing.

In the modern era, psychotherapy has followed a tortuous and often crazy path right up to the present day where, hopefully, it has settled into some kind of sense.

The origins of modern psychotherapy

Psychotherapy and sophisticated psychological understanding are far from exclusively Western domains.

Western orientalists have noted that Sufi literature is full of evidence of profound psychological insight and sophisticated psychotherapeutic procedures. Historical Sufis such as Jalaludin Rumi of Afghanistan and El Ghazali of Persia display psychological understandings that have only recently been paralleled in the West.1

In addition, ancient Egyptian and Greek writings dating back over 3,500 years talk of ‘healing through words’, and the word counselling was used as early as 1386 in Chaucer’s The Wife of Bath’s Tale.2

Words can heal, but also baffle. So let’s get simple.

What are we talking about exactly?

These days, the terms ‘counselling’ and ‘psychotherapy’ are often used as if they are different things. But of course both psychotherapy and counselling simply mean helping someone using psychological means. Sure, there may be different emphasis in, say, solution-focused counselling versus person-centred counselling. But the objectives are similar: happier, better-adjusted people.

In no other sphere of life, except maybe politics and religion, have words and language so confused the essential issues. To understand psychotherapy and the different ideas about it, we need to look at some of the changing presuppositions about how the mind works. It’s a truly fascinating journey.

To kick us off, here’s a really interesting way of looking at this.

Changing metaphors for the mind

Writers such as Frank Tallis3 and Robert Ornstein4 have pointed out that psychological ideology has long tried to vie for scientific legitimacy with other ‘harder sciences’, even to the point of borrowing metaphors from impressive technological innovation.

In the early years this may have been done (consciously or otherwise) to help cement psychology as one of those hard sciences.

But interestingly, even today we continue to use and even think in terms of technological metaphors when we talk about emotions.

See if these ring any Pavlovian bells.

Hysterical hydraulics

During the 18th and 19th centuries the technology of hydraulics really steamed ahead. James Watt and other inventors had developed the steam engine, and rail travel was transforming the world.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the metaphor for the mind, too, had become to a large extent hydraulic.

People talked, and still talk, of ‘running out of steam’, ‘letting off steam’, and ‘releasing pent-up emotion’. Much experimental therapy (particularly in California during the 1970s) focused on the hydraulic metaphor, believing that to truly grow, a person had to ‘vent’ all their ‘bottled-up’ feelings.

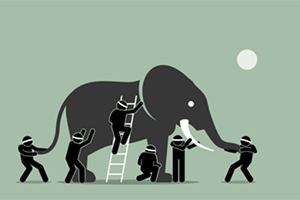

As with all the different therapeutic factions, there is some truth in this. (I am reminded yet again of the ancient parable of the blind men and an elephant.)

‘Expressing’ (another hydraulic term) may have value for some people, particularly if they have never or seldom communicated how they feel. But we have to be careful.

Recent physical tests of heart and immune function show that releasing extreme anger is just as toxic to the heart and immune system as ‘keeping the anger in’.5

Continually expressing our emotions may only serve to increase our proneness to experience these emotions. And if those feelings are ones of sadness, resentment, or anger, that puts us in dangerous territory.

So the simplistic idea of expressing emotions, one that may sometimes help some people, came to be seen as a kind of panacea – but with little evidence of therapeutic efficacy.

Here’s another metaphor you may have heard.

Going ‘deep’

When we use the metaphor of problems being ‘deep rooted’ or ‘deep seated’, we’re really talking about any explanation of behaviour that exists at the level of the unconscious.

Freudian and Jungian analysis are classic examples of ideologies that assumed that much or even all human behaviour could be explained at a ‘deeper’ level.

People sometimes use the depth metaphor to describe the severity or seeming intractability of an emotional problem: “Oh, I think it runs a little deeper than that!”

Similarly, the tree root metaphor is often used when we feel that it might be too superficial to talk in terms of helping lift symptoms: “But we need to get to the root of the problem!”

But simply talking about ‘the root of the problem’ and actually recognizing it are two different things. And – to extend the metaphor – helping to ‘uproot’ the cause is another thing again.

‘Uprooting’ the origins of a problem really just means coming to a realization of why it formed, and thereby developing insight. But again, there is no evidence that knowing why (or thinking you know why) you have, say, an alcohol problem will act as a magical cure and stop you drinking. I’ll come back to this in a moment.

So what technology came next? Ah yes, the lightbulb moment! You might recognize these metaphors too.

Electrifying ideas

After hydraulics came electricity, which was, by the early 20th century, becoming a big factor in industrialized society. People talked of ‘recharging your batteries’, ‘being run down’ and ‘feeling flat’. And they still do.

Psychiatrists at the Tavistock clinic in London routinely electrocuted British survivors of World War I trench warfare in an attempt to restore their energy levels, and electroconvulsive ‘therapy’ became popular.6 Ironically, electrical psychiatry killed some survivors of the Somme.7

Then psychology tried to hitch a lift on the back of something else.

Does not compute

After World War II came the computer age. Computers had proved their worth during wartime as code-breaking devices, and a new metaphor for the human mind was borne. We now talk of ‘processing information’, ‘retrieving memory’, and ‘crashing’.

The brain came to be seen as ‘like a computer’, or perhaps it was the other way around: people thought computers were a bit like the human brain.

But things have moved on.

New scanning techniques have advanced the study of the human brain tremendously over the past few decades. We now have a direct understanding, unparalleled in history, of how the brain works. It seems to be that metaphorical references to current technologies may no longer be necessary.

However, I do think all the metaphors I’ve mentioned had their uses, and were partly accurate in some ways.

So ends a brief and enormously broad look at the history and development of some psychological ideas. So what of psychotherapy?

Hypnotic beginnings

The so-called ‘Father of Western Psychotherapy’ was Viennese physician Franz Mesmer.8 In the 18th century he pioneered hypnotherapy as a treatment for psychosomatic problems and other disorders of the mind.

His technique become known as ‘mesmerism’, or sometimes ‘animal magnetism’. The term hypnosis was not yet used.

While Mesmer’s treatments and techniques were often successful, his overly mystical rationale as to why they were effective tainted perceptions of hypnosis somewhat. His talk of ‘animal magnetism’ and ‘universal fluid’ was at odds with the rise of ‘respectable’ science during the 18th century.

The next big thinker on the scene (and yes, I’m missing out other contributors) was a cigar-chomping, one-track thinker – and also an Austrian.

Psychotherapy gets fixated

Sigmund Freud is perhaps the most famous promulgator of psychological theory in recent history. His way of understanding the mind is called psychoanalytic, and until recently his ideas strongly influenced how people thought psychotherapy should be carried out.

Freud started off using hypnosis, but was very eager to pioneer his own approach. He began his career by publishing a paper on cocaine as a “cure all”, asserting that it could cure depression, gastric catarrh, indigestion, severe vomiting, and morphine addiction. (Freud believed cocaine to be non-addictive.) He commented on the “gorgeous excitement” that animals displayed after being injected with the “magical substance”.

After realizing that cocaine had certain shortcomings, Freud tried to establish nasal surgery as an effective treatment for “hysterical symptoms” and female masturbation. But after the near death of a female client who had been operated on by a friend of his, he changed his approach.

After these rather dubious beginnings, Freud was heavily influenced by the work of Jean-Martin Charcot, a famous French neurosurgeon who carried out research on hypnosis in highly hypnotizable subjects, and on hysteria.

Freud became fascinated by the unconscious underpinnings of what makes us all tick.

Unconscious understandings

Freud believed that much of our behaviour is unconsciously motivated, which on the face of it seems a reasonable idea. However, his version of the unconscious was a seething cesspool of repressed desires and fears. A more modern understanding of the unconscious mind sees it as potentially highly resourceful – not just a garbage can for all our scandalous thoughts and wishes.9

Freud correctly ascertained that the human brain works metaphorically, but sought to assign the same metaphors to everybody (namely those from the ancient Greek tradition).

He also proposed arbitrary divisions of the mind: ego, superego, and id. He felt that infants pass through oral, anal, and phallic stages, and that individuals could become ‘stuck’ in one of these stages, with dire consequences. Such an individual, he believed, would then have to undergo long-term, expensive psychoanalysis.

Freud also believed that little boys want to kill their fathers and have sex with their mothers (Oedipus complex), and that they fear being found out and having their penises cut off (castration complex).

Even more disturbingly, Freud thought children’s reports of sexual abuse were sometimes “wish fulfillment” fantasies – yet another example of how ideas can potentially have dangerous real-world consequences.

In fact, Freud attached sexual significance to much of everyday life, although when confronted with the possibility that perhaps his beloved cigar was really a phallic symbol he allegedly stated that “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.” Maybe he was in denial!

More mistakes from Freud

Freud changed and modified his ideas so much that a study of his theories can be quite confusing. His ideas about the purpose of dreaming, for example, are naive and inconclusive compared to modern understandings.10

None of Freud’s theories were based on any kind of research, so psychoanalysis cannot really be called a science. There is no evidence that Freud ever helped anybody therapeutically, or that psychoanalysis is at all effective in the treatment of psychological problems.11

But Freud’s belief system was interesting and new, and it held sway over much 20th-century thinking. Many physical complaints, such as epilepsy, Tourette Syndrome, and concussion due to closed head injury, were attributed to emotional ‘hysteria’ and treated psychologically rather than physically.

The great influencer of Freud, Martin Charcot, once examined a man who had been brain damaged after being sideswiped by a fast-moving carriage. The man suffered terrible headaches, nosebleeds, and even seizures, but because he didn’t look injured on the outside Charcot assumed these symptoms were caused by emotional repression of the trauma of the accident (which the man couldn’t recall).

Thus was born the idea of repression of terrible events – one of Freud’s most notable legacies. Of course, these days we have a much better understanding of how physical brain damage can cause memory loss.12

But maybe it’s not what you think or repress, but what you do that counts.

The rise of behaviourism

Perhaps as a backlash to the rather colourful ideas and practices of psychoanalysis, behaviourism developed the theory that mental processes were irrelevant (the first of several cases within psychotherapy of throwing the baby out with the bath water).

The useful insight here, propagated by the likes of B. F. Skinner, was that encouraging healthy behaviours made people feel better, which is borne out by modern research (and common sense).13

Techniques of behavioural therapy sometimes involved giving people electric shocks in conjunction with, say, drinking alcohol so that drinking would come to be associated with pain.

Behaviourism as an exclusive approach is questionable to say the least. ‘Pure’ behaviourists believed that there was no such thing as mind or consciousness, only behaviour.

I’ll get to cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in a moment, but first a timely reminder that psychological therapy is always all about the client.

Person-centred counselling

Another chapter in the psychotherapeutic story was the idea, developed by people such as Carl Rogers, that the relationship between practitioner and client was centrally important. A practitioner was, ideally, non-judgemental and non-prescriptive.

It’s a beautiful idea: that person-centred therapy – passive acceptance and empathetic understanding – would somehow encourage ‘self-actualization’, a state of being in which the client becomes fully emotionally integrated. People were likened to flowers, who would bloom if given the right environment and space to grow.

Some clients, though, become frustrated by a lack of dynamic direction from the therapist or counsellor. Person-centred counselling, not surprisingly, has poor outcomes for the treatment of depression or trauma.14 Yes, clients need to be supported and listened to and given respectful space to tell their stories. But that is not all they need.

We now know rumination is toxic for depression,15 so it follows that endlessly encouraging reflection in our depressed clients may actually make them worse.

The capacity to empathize and give our clients room to discuss their feelings is, of course, useful as an isolated skill. But it’s certainly not the whole picture.

Is insight in sight?

The idea with many of the therapeutic ideologies we’ve discussed (pure behavioural therapy excepted) is that when a person gains ‘insight’ – when they come to an understanding or interpretation of why they have a problem – the problem will somehow dissolve.

While it may be helpful to know where, for example, a phobia came from, it’s unreasonable to expect that this will spell the end of the problem. We know that the emotional centres of the brain (housed within the limbic system) and the thinking centres (housed in the neocortex) are quite separate and distinct in many ways.

In other words, intellectual understanding of an emotional problem rarely makes a difference to the emotional problem itself. Although, sometimes seeing how the problem operates objectively does seem to be able to interrupt its pattern, in my experience anyway.

None of this is to say that one part of the brain doesn’t influence the other, but if emotion is very intense, then discovering a rationale for why it occurred will not in itself supply the skills to actually dissolve that over-emotionality.

Millions of people know why they have a phobia, why they are depressed, or why they suffer terrible flashbacks, but rarely does this ‘insight’ actually help. Indeed, it’s been said that insight therapy was so called because the end to such therapy was never ‘in sight’.

So what other routes did therapeutic ideas take?

Cognitive therapy arrives on the scene

More recently, Aaron Beck, inspired by the ancient writings of the reflective Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, developed cognitive psychotherapy.

Beck, who had been a Freudian, helped devise the central premise of cognitive psychotherapy – that what we think dictates what we feel. The practical idea is that getting people to challenge their assumptions and thinking can lend them control over their emotional life and lead to less damaging ways of living.

I would say getting people to desist from unrealistic assessments of their lives and to use their cognitive brain effectively can be highly effective, especially in the treatment of depression.

But there are problems with the old idea that thoughts inevitably guide feelings.

Gaps in cognitive theory

Thinking does not always precede emotion. Sometimes it’s the other way around, as Daniel Goleman points out in his groundbreaking book Emotional Intelligence.16

When, for example, we jump at a sudden noise, our emotional response comes about half a second before the thinking brain produces the thought “Oh, the car backfired!” We don’t think “The car backfired” and then, because of that thought, feel a rush of fear.

All experience, in fact, seems to come with an emotional ‘tag’. Having said that, cognitive therapy, while sometimes being guilty of over-complexity, certainly can help people use the cognitive parts of their brains to still and question emotional impulses – as long as those impulses aren’t too overwhelming.

Anxiety, anger, depression, and many other psychological conditions are as much disorders of the imaginative mind as of the cognitive or thinking mind. Which brings us full circle back to Mesmer and the use of therapeutic hypnosis, in conjunction with other approaches, to facilitate positive change in people. Hypnosis is unparalleled in its ability to engage the imaginative mind and use it constructively.

Cognitive therapy has been combined with behavioural therapy to form cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). This approach has certainly gained attention as a more effective treatment for depression than person-centred counselling or psychoanalysis.

However, recently the efficacy of CBT for depression has been questioned. It seems there may have been a placebo effect due to the newness and positive publicity surrounding CBT, which is now apparently 50% less effective at treating depression than it was a few years ago.17

But what of the future of therapy?

In search of solutions

Dr Milton Erickson was a revolutionary of his time. He looked for solutions to patient problems, not just diagnoses or explanations as to the genesis of those problems.

Erickson focused on the patient within the wider context of their lives, such as their families, and he focused on symptom relief as a way of affecting the causes of those symptoms. He also worked as briefly as possible, sometimes effecting cures in a single session. In an age when all these ideas amounted to blasphemy, he was brave and effective indeed.

Since his time, solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) has really taken off. Because it tends to be time limited, the risks of the client becoming too reliant on the therapist or vice versa is greatly diminished.

So where are we going with all this?

Cutting-edge therapy and being human

In a remarkable effort to extract what actually works from the messy history of psychotherapy, the Human Givens approach has done more than anyone else to align science to psychotherapy.

In brief, this approach examines how the sciences, such as biology, brain research, social research, and anthropology, align with common sense to produce an accurate picture of the common needs and characteristics of human beings.

So rather than concocting a mythology or complex ideology and then trying to get people to fit the ideology, they look at what we know about people and identify the common effective factors in different therapeutic approaches.

They see people as having basic emotional needs which ‘seek completion’ in the environment.

Any psychological problem can be traced back to one or more needs not being met in a person’s life. This can occur either though innate problems such as autism, environmental problems such as unsafe surroundings, or emotional conditioning.

A person may feel better going along to see a psychotherapist because it fulfils a need not being met elsewhere in their life, such as the need for attention, intimacy or purpose. But if the therapist believes the improvement is down to ‘uncovering a penis envy complex’, or ‘getting in touch with the inner child’, or ‘strengthening the id’, confusion inevitably results.

When we are clear about our human needs, we can also be clear about the origin of problems.

An effective therapist will seek to teach the patient to ensure their own needs are met away from the therapist’s office. After all, the real aim of a therapist should be to become redundant in the patient’s life, not central to it!

The Human Givens approach recognizes the resources nature gave us to seek out the fulfilment of our needs, including:

- the ability to develop complex long-term memory

- an imagination that allows us to focus attention away from emotions in order to problem-solve objectively

- the ability to understand the world through metaphor (‘complex pattern matching’)

- an ‘Observing Self‘ – a unique centre of awareness within us that can take a step back and watch our own psychological and physical processes

- the ability to empathize and connect with others

- a rational mind to check our emotions

- a dreaming brain that preserves mental and physical health by metaphorically defusing emotionally arousing introspections not acted out the previous day.

It seems that to be effective, therapists need to focus on client resources and potential solutions at least as much as pathology and causes.

Therapy needs to be time limited and as brief as possible. We need to sometimes listen, sometimes challenge beliefs, sometimes teach skills, sometimes focus on the client’s behaviour, and sometimes focus on their thoughts – but not always before helping them with their feelings.

Human beings are not flowers. Nor are they purely thinking or behavioural machines, or seething subconscious masses of Freudian Greek metaphors. We are an interesting blend of the behavioural, social, physical, metaphorical, cognitive, unconscious, and emotional. And it is to all these that good psychotherapy will apply.

The philosophy of psychotherapy has finally changed, or perhaps come full circle. If observation can come before theory, then theory can become a practical basis for providing real help to real people in the real world.

It needn’t be confusing.

Get a fresh approach with Uncommon Psychotherapy

And if you’re looking to boost your therapeutic confidence, our Uncommon Psychotherapy course will give you the skills to see clearly what your clients need. Uncommon Psychotherapy is free inside Uncommon Practitioners TV, and you can sign up to be notified when UPTV is open for booking here.

Notes:

- See Idries Shah’s seminal book The Sufis. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sufis

- See Staying sane: How to make your mind work for you, by Dr Raj Persaud. https://www.amazon.com/Staying-Sane-Make-Your-Mind/dp/1900512386.

- See The history of psychotherapy: Hidden minds. https://www.amazon.com/Hidden-Minds-Unconscious-Frank-Tallis/dp/1559706430

- See http://www.robertornstein.com/books.html

- https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Wenneberg+SR,+Schneider+RH,+Walton+KG,+et+al.+Anger+expression+correlates+with+platelet+aggregation.+Behav+Med+1997;22:174%E2%80%937

- https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/war_psychiatry

- https://files.ondemandhosting.info/data/www.cchr.org/files/The_Brutal_Reality.pdf

- I recommend The wizard from Vienna: Franz Anton Mesmer, by Vincent Buranelli. https://www.amazon.com/wizard-Vienna-Franz-Anton-Mesmer/dp/0698106970

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/daviddisalvo/2013/06/22/your-brain-sees-even-when-you-dont/#61651cc5116a

- See Dreaming Reality: How dreaming keeps us sane or can drive us mad, by Joe Griffin. https://www.uncommon-knowledge.co.uk/book_review/dreaming_reality.htm

- See Why Freud was wrong: Sin, science and psychoanalysis, by Richard Webster. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Why_Freud_Was_Wrong

- https://www.webmd.com/baby/news/20030131/even-mild-concussions-cause-memory-loss-in-high-school-athletes#1

- https://www.spring.org.uk/2007/08/how-to-change-bad-mood-raise-energy-and.php

- See http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1996-14973-001. This huge meta-study of over 100,000 pieces of depression research recommends that the first-line treatment for depression should be appropriate psychotherapy, even when the depression is severe.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-24444431

- http://www.danielgoleman.info/topics/emotional-intelligence/

- https://uit.no/Content/418448/The%20effect%20of%20CBT%20is%20falling.pdf